***The Beatles’ album, Revolver, was released 50 years ago today. I was not aware of this of course, until Maxime told me about it. So here’s his article on this great album! ***

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the Beatles’ album Revolver. A seminal recording which saw the Fab Four at the peak of their musical inspiration. Equality reigns on this album, as on no other Beatle record: Lennon has five tracks, McCartney six, Harrison three. There is even a vocal appearance by Starr (the well-known ‘Yellow Submarine’). But the drummer’s most important input on this disc, is indeed the drum itself. Starr is at the peak of his energy here, which is enhanced by the recording process.

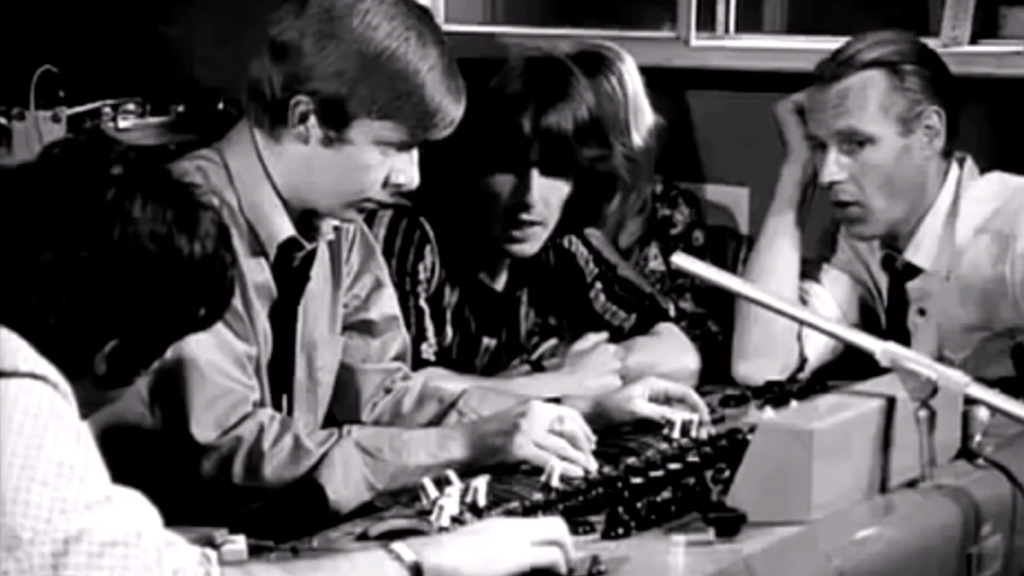

While I’m far from an expert on the matter of recording techniques, I have read a few things about how this incredible drum sound was achieved. It is mainly the feat of Geoff Emerick, a newly appointed sound engineer, who was only 20 years old at the time. Breaking all the golden rules that applied at EMI then, Emerick decided to record ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ by placing the microphone (an AKG D20) three inches from the kick drum (instead of eighteen inches). Because the mic was so close to the source, he risked saturation and maybe breaking the mic. To avoid this, he stuffed a big sweater inside the drum, and made the signal go through a Fairchild compressor.

A compressor is used, well, to compress the sound, i.e to reduce the volume difference between the loudest sound and the faintest. This difference is called the signal’s dynamic. By working on the dynamic, the engineer can capture both the loudest bangs and the faintest chirps, without straining our ears. On some compressors, especially vintage ones like the one Emerick used, the sound can acquire a ‘pump-like’ quality, as if it were sucked in and out of a tube. This is caused by a latency in the compressing process: the compressor takes a few milliseconds to ‘understand’ that the sound goes from faint to loud, or from loud to faint.

On ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, Emerick used a compressor on both drum mics (the other one is an AKG D19, placed overhead), and he exaggerated the pumping. As a result, the drums feel like they’re being sucked into another world, and perfectly match the song’s intended impression. The Fabs were reportedly very impressed by this achievement, especially Starr, and Emerick’s innovation has paved the way for what is now called normality, aka: close-miking (or putting the microphone close to the source).

For a lot of other instruments, close-miking gives a visceral feel to the signal, which provides it with an incredible presence. Indeed, a close-miked signal observes a bump in low-mid frequencies (from 200 to 500 Hertz), and therefore sounds warmer. Before then, Pop production rules were loosely set from the recording process of classical music, which would put the microphones in the spectator’s seat (roughly). This is why, to our modern ears, a lot of drums from the 50s and the 60s sound far away, almost absent, and generally buried among the other instruments. This is typical of Phil Spector’s style of production, for instance.

One has to understand that Emerick’s innovation was especially bold, considering that he was one of the youngest members of Abbey Road’s staff, and that ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ was his very first try as an engineer for the Beatles. His revolutionary methods earned him an EMI reprimand at first, but literally tore studios apart later on. This also caused an earthquake in the microphone industry, which now had to include PADs on their products. A PAD is an internal device that limits the incoming signal, to avoid saturation. Close-miking was also used on the strings of ‘Eleanor Rigby’: the string quartet was reportedly apprehensive of the foreign device being placed so close to them, and would regularly pull back their chairs in-between takes.

Although I have a million things to say about this album, I’ve decided to focus on this underrated aspect of the recording process. We often tend to forget that incredible sound technicians and engineers, like Geoff Emerick, were essential in crafting an artist’s sound, even though they were seldom credited on album sleeves. Fortunately, Emerick’s work got publicly acknowledged two years after Revolver, with Sgt. Pepper earning him a Grammy Award for best recorded album.

No Comments